New Jersey Parents’ Views of Adolescent Depression Screening

There is an alarming increase in the percentage of U.S. adolescents reporting depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation, including in New Jersey. Early detection and treatment are key to preventing negative, long-term effects of depression in youth, and current guidelines recommend routine screening for depression in adolescents ages 12-18. Yet rates of adolescent depression screening remain extremely low. Our research shows that parents in New Jersey recognize the benefits of depression screening but have concerns regarding possible unintended effects and the administration of screening in schools. Effective communication that addresses these concerns is imperative to increasing support from parents to school-based depression screening.

WHAT IS THE PROBLEM:

According to a 2021 Surgeon General’s Advisory,[i] there has been a recent increase in certain mental health symptoms among U.S. adolescents, including depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation. From 2009 to 2019, the proportion of high school students reporting persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness increased by 40%, and the share of those seriously considering attempting suicide increased by 36%. An analysis of 2018 and 2019 data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) reveals a similar upward trend in depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation among adolescents in New Jersey.[ii] Rates of psychological distress among young people, including symptoms of anxiety, depression, and other mental health disorders have generally increased since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.[iii]

Current US Preventive Services Task Force’s guidelines recommend universal screening for depression in adolescents ages 12-18.[iv] Research suggests that while nearly one in five school-age adolescents in the U.S. have a diagnosable psychiatric disorder, the majority of mental health problems are undetected and untreated, in part because adolescent depression screening rates remain extremely low.[v] Screening adolescents for major depressive disorder in primary care settings offers a potential venue for improving universal access to screening, but screening in this setting remains consistent with persistent inequalities by race, ethnicity, and region.[vi]

School-based depression screening may address a number of access-related barriers: they are less stigmatizing, provide an opportunity to target problems before they reach diagnostic criteria, and promote access to care for underserved populations such as minority youth.[vii] There is evidence that school-based screening programs can be effective in improving early detection and treatment of depression,[viii] but critical barriers remain.[ix] Many school administrators express concerns regarding the feasibility of obtaining parental consent for screening,[x] and available estimates show that about one-third of parents do not consent to depression screening.[xi]

WHAT WE DID:

We conducted a survey with a representative sample of 678 parents of adolescents ages 12-18 in New Jersey in March 2022.

WHAT WE ASKED:

We asked parents about (a) their degree of concern regarding their child’s risk for depression and suicide; (b) their degree of confidence to identify depression/suicidality symptoms and to seek help when symptoms are detected; (c) their beliefs regarding the potential benefits and potential undesirable outcomes of depression screening in school; (d) their specific concerns regarding administration of screening; and (e) how likely they are to consent for their child to be screened for depression in school.

WHAT WE FOUND:

About 25% of all parents interviewed (N = 678) said they are very concerned, and another 26% said they are moderately concerned, about their child’s risk for depression. By comparison, 16% said they are very concerned, and another 15% said they are moderately concerned, about their child’s risk for suicide. There were statistically significant differences in how parents from different race/ethnicity group responded to these questions. Specifically, a greater percentage of Hispanic parents (55.4%, n = 159) said they are very or moderately concerned about their child’s risk for depression compared to 52.3% of Whites (n = 348), 48.6% of Blacks (n = 72), and 51.4% of parents from another race (n = 85). Hispanic parents were the most likely to say they are very or moderately concerned about their child’s risk for suicide (41.9%), followed by Black parents (36.1%), White parents (27.9%), and parents from another race (22.4%).

Overall, a majority of parents (67.7%) said they are very or moderately confident they can detect symptoms of depression in their child and 57.8% said they are very or moderately confident they can detect symptoms of suicidality. There were statistically significant differences in how parents from different race/ethnicity group responded to these questions. Specifically, Hispanic parents were less likely to say they are very or moderately confident they can detect symptoms of depression (62.1%, compared to 67.5% of Whites, 79.2% of Blacks, and 67.5% of parents from another race). They were also likely to say they are very or moderately confident they can detect symptoms of suicidality (51%, compared to 60.5% of Whites, 59.7% of Blacks, and 58.9% of parents from another race).

A majority of parents said they are very or moderately confident they know where to turn to for professional help if their child is showing symptoms of depression (72.3%) and also suicidality (71.3%). Hispanic parents (67.7%, compared to 76% of Whites, 78.1% of Blacks, and 72.2% of parents from another race) where less likely to express confidence regarding knowing where to turn to for professional help if their child is showing symptoms of depression (a statistically significant difference), but similar to other groups regarding suicidality.

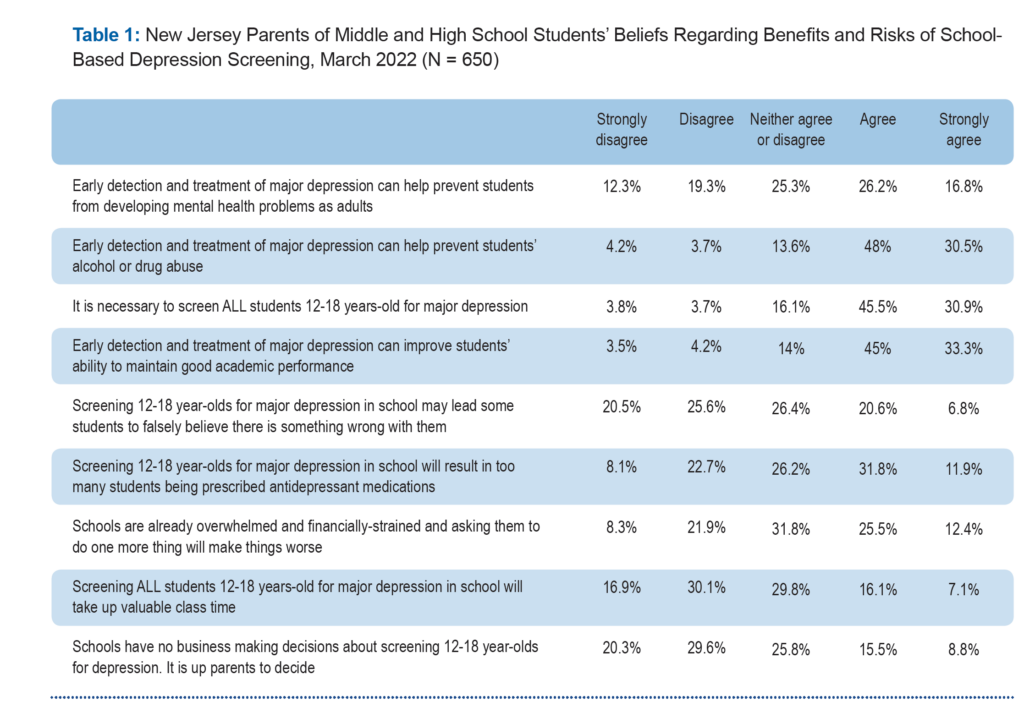

Table 1 summarizes the distribution of responses parents gave to survey items assessing their level of agreement or disagreement with statements regarding potential benefits and risks of depression screening. It is apparent that a majority of parents in the state agree or strongly agree that depression screening is beneficial in terms of its potential to prevent the development of mental health problems as adults (43%), potential alcohol and drug abuse (78.5%), and academic problems in school (78%). A majority (76.4%) also agree or strongly agree that it is necessary to screen all students ages 12-18 for major depression. At the same time, a nontrivial percentage of parents also agree or strongly agree that depression screening in school can have undesirable outcomes including leading some students to believe that something is wrong with them (27.4%), too many students being prescribed antidepressant medications (43.7%), increasing the financial burden on schools (37.9%), and taking up valuable class time (23.2%). About 25% of parents agree or strongly agree that schools should have no role in screening students for depression. Hispanic parents were significantly more likely to agree or strongly agree that screening will increase the financial burden on schools (42.4%, compared to 35.6% of Whites, 32.9% of Blacks, and 38% of parents from another race).

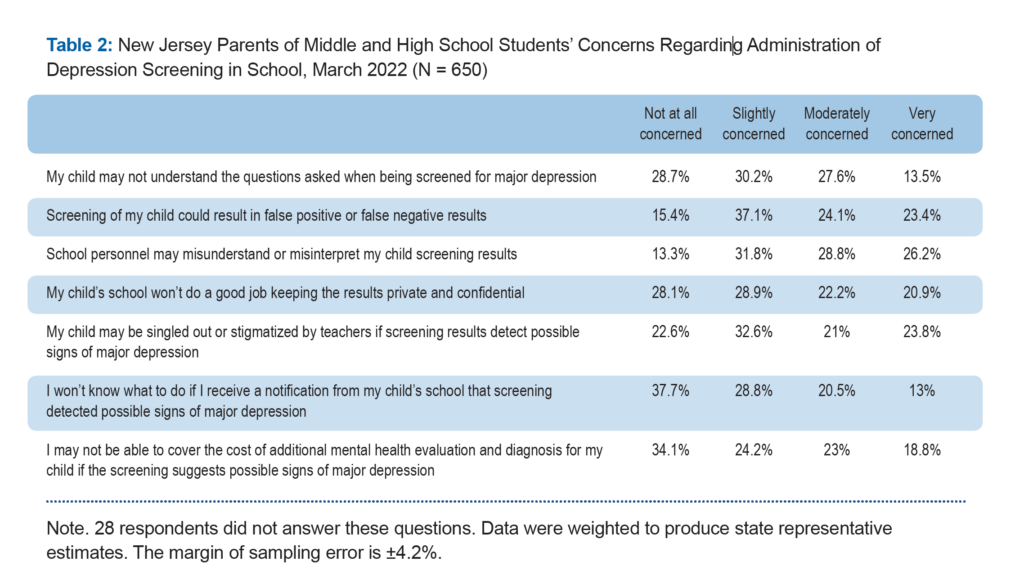

Table 2 summarizes the distribution of responses parents gave to items assessing their level of concerns regarding the administration of depression screening in their child’s school. About 41% of all parents said they are very or moderately concerned about their child not understanding the questions used for screening and 47.5% expressed concerns about false positive or negative results. More than half (55%) said they are very or moderately concerned about school personnel misinterpreting results and 43.1% are concerned that the school will not do a good job keeping the results private and confidential. About 45% of parents said they are very or moderately concerned about their child being singled out or stigmatized by teachers if signs of depression are detected. About one-third of parents expressed concern about not knowing what to do if they receive a notification from their child’s school about a positive screening result, and 41.8% said they are concerned about being able to afford the cost of additional evaluation and diagnosis.

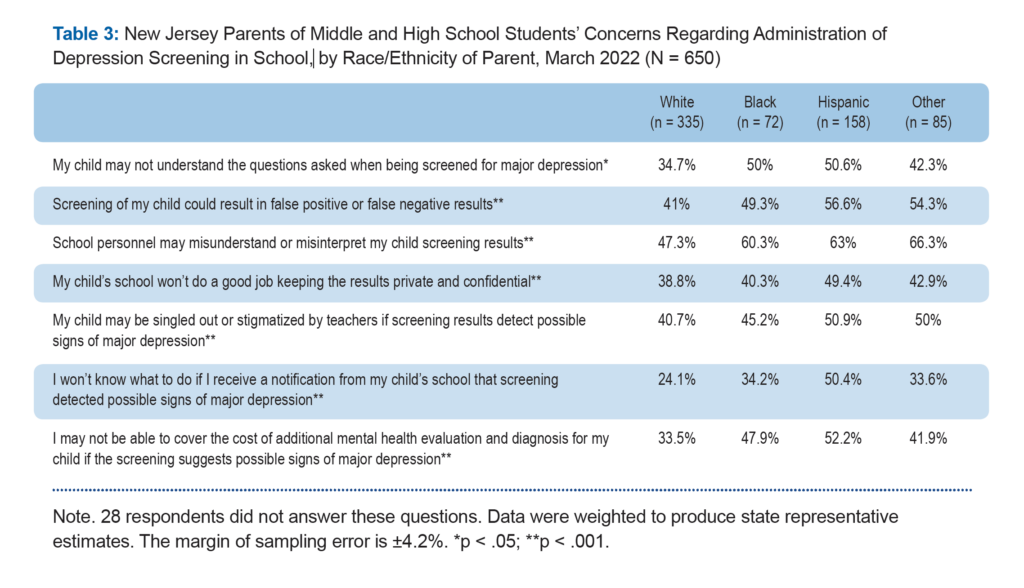

Table 3 compares the distribution of percentages of parents from different race/ethnicity group who said they are very or moderately concerned about each of the concerns listed in Table 2. The findings show that non-White parents were significantly more likely than White parents to express concerns regarding the ability of their child to understand the screening questions, the possibility of false positive or negative results, misinterpretation of screening results by school personnel, privacy and confidentiality of results, and potential stigma. Non-White parents, and Hispanic parents in particular, were also disproportionally concerned about not knowing how to follow up on a notification of a positive result and their ability to afford additional mental health evaluation and diagnosis if screening suggests their child may need one.

Finally, parents were asked to indicate their likelihood of giving school permission to screen their child for depression if asked to do so. About one-third (32.4%) said they are very likely to do so, 33.5% said they are likely, 7.1% said they are unlikely, and 12.3% said they are very unlikely to do so. About 15% said they are not sure. There were no statistically significant differences in the responses to this question given by parents from different race/ethnicity, income, and education groups. However, there was a statistically significant difference by region of the state: A greater percentage of parents from shore communities (29.9%) and the south (22.8%) said they are unlikely or very unlikely to consent to depression screening of their child in school compared to parents from urban (9.2%), suburban (16.9%), and exurban (20.6%) regions of the state.

WHAT IT MEANS:

The great majority of parents in the state (over 75%) recognize the value of depression screening in preventing adolescents from developing serious mental health issue, drug and alcohol abuse, and poor academic performance. A majority (76.4%) also agree or strongly agree that it is necessary to screen all students ages 12-18 for major depression. However, between 25%-45% of all parents perceive potentially undesirable outcomes of screening including leading some students to believe that something is wrong with them, too many students being prescribed antidepressant medications, increasing the financial burden on schools, and taking up valuable class time.

Close to half of all parents are very or moderately concerned about the administration of screening in school, specifically, that their child will not understand the questions used for screening, false positive or negative results, school personnel misinterpreting results, school not doing a good job keeping the results private and confidential, and their child being singled out or stigmatized by teachers. About one-third of parents expressed concern about not knowing what to do if they receive a notification from their child’s school about a positive screening result and about 42% said they are concerned about being able to afford the cost of additional evaluation and diagnosis. These concerns are particularly acute among Black and Hispanic parents and are consistent with the growing incidence of depression and suicide among Black, Hispanic, and Asian adolescents as well as with existing disparities in access to mental health services for these minority populations.

The findings of this study underscore the need for effectively addressing parents’ concerns regarding the potential harmful effects of depression screening as well as common concerns regarding the administration of screening in school. Specifically,

- In this updated review, USPSTF found no direct evidence to support concerns regarding the harms of screening on adolescents, and it may be worthwhile to communicate this to parents.

- It is also critical to ensure parents that screening administration will be conducted in a way that ensures privacy and confidentiality, accommodates students with specific needs, and allows for real-time evaluation of the results and intervention by a licensed mental health professional.

- Schools notifying parents of a screening result indicating a student may be experiencing depression should ideally also advise the parents of available services or resources for further evaluation and diagnosis of their child, including information about cost and available insurance to cover expenses.

- Parents who decline to consent for their child to be screened for depression in school should be encouraged to seek screening in pediatric setting, if they feel more comfortable doing so.

METHODOLOGY:

The statewide survey of New Jersey parents/guardians of adolescents aged 12 to 18 years (N = 678) was fielded by Rutgers University’s Eagleton Institute of Politics, Eagleton Center for Public Interest Polling (ECPIP) in March 2022. Respondents were recruited from a combination of probability-based and listed sample frames. The data were weighted to represent adult parents in New Jersey households who live with a child aged 12-18 who are in school. Weighting parameters were derived from 2019 American Community Survey PUMS data. The variables used in calibration were sex, education, race/ethnicity, and region. The margin of error for the total sample is ±4.2 percentage points. This means that in 95 out every 100 samples using the same methodology, estimated proportions based on the entire sample will be no more than 4.2 percentage points away from their true values in the population.

The sample of parents interviewed was 53.4% females and 52.3% White (10.9% Black, 24.2% Hispanic, and 12.7%, Asian or Pacific Islander, American Indian or Alaska Native, or other race). About 46% had a college degree or a higher level of education (22.9% some college, 22.1% high school graduate, and 9.4% less than high school education). Regarding household income, 42.2% reported an income lower than 75k, 32.8% income between 75k-150k, and 25% an income greater than 150k).

[i] Office of the Surgeon General (OSG). (2021). Protecting Youth Mental Health: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory. US Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-general-youth-mental-health-advisory.pdf.

[ii] KFF analysis of Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)’s restricted online data analysis system (RDAS), National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), 2018 and 2019, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Data Archive. https://www.kff.org/statedata/mental-health-and-substance-use-state-fact-sheets/new-jersey/.

[iii] Cloutier, R. L., & Marshaall, R. (2021). A dangerous pandemic pair: Covid19 and adolescent mental health emergencies. The American journal of emergency medicine, 46, 776–777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2020.09.008.

[iv] Siu, A. L., & US Preventive Services Task Force (2016). Screening for Depression in Children and Adolescents: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Pediatrics, 137(3), e20154467. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-4467.

[v] Sekhar, D. L., Ba, D. M., Liu, G., & Kraschnewski, J. L. (2019). Major Depressive Disorder Screening Remains Low Even Among Privately Insured Adolescents. The Journal of pediatrics, 204, 203–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.07.086.

[vi] Sekhar, D. L., Schaefer, E. W., Waxmonsky, J. G., Walker-Harding, L. R., Pattison, K. L., Molinari, A., … & Kraschnewski, J. L. (2021). Screening in High Schools to Identify, Evaluate, and Lower Depression Among Adolescents: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA network open, 4(11), e2131836-e2131836. https://doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.31836.

[vii] Volpe, R. J., & Briesch, A. M. (2018). Establishing evidence-based behavioral screening practices in US schools. School Psychology Review, 47(4), 396-402. https://doi.org/10.17105/SPR-2018-0047.V47-4.

[viii] Soneson, E., Howarth, E., Ford, T., Humphrey, A., Jones, P. B., Thompson Coon, J., Rogers, M., & Anderson, J. K. (2020). Feasibility of School-Based Identification of Children and Adolescents Experiencing, or At-risk of Developing, Mental Health Difficulties: a Systematic Review. Prevention science, 21(5), 581–603. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-020-01095-6.

[ix] Burns, J., & Rapee, R. (2021). From barriers to implementation: Advancing universal mental health screening in schools. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools, 31(2), 172-183. https://doi:10.1017/jgc.2021.17.

[x] Moore, S. A., Dowdy, E., Hinton, T., DiStefano, C., & Greer, F. W. (2022). Moving Toward Implementation of Universal Mental Health Screening by Examining Attitudes Toward School-Based Practices. Behavioral Disorders, 47(3), 166–175. https://doi.org/10.1177/0198742920982591

[xi] Husky, M. M., Sheridan, M., McGuire, L., & Olfson, M. (2011). Mental health screening and follow-up care in public high schools. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 50(9), 881-891.