Call for Action On Adolescent Depression: What Do Schools In New Jersey Need To Identify And Support Students At Risk For Depression?

WHAT IS THE PROBLEM:

There is an alarming increase in the percentage of U.S. adolescents reporting depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation, including in New Jersey. Early detection and treatment are key to preventing negative, long-term effects of depression in youth, and current guidelines recommend routine screening for depression in adolescents aged 12-18. Yet rates of adolescent depression screening remain extremely low. School-based programs can be an effective tool for improving rates of screening and early identification of adolescent depression, but critical barriers to implementation remain that can be addressed via sound policy.

According to a 2021 Surgeon General’s Advisory,[i] there has been a recent increase in certain mental health symptoms among U.S. adolescents, including depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation. From 2009 to 2019, the proportion of high school students reporting persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness increased by 40%, and the share of those seriously considering attempting suicide increased by 36%. An analysis of 2018 and 2019 data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) reveals a similar upward trend in depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation among adolescents in New Jersey.[ii] Rates of psychological distress among young people, including symptoms of anxiety, depression, and other mental health disorders have generally increased since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.[iii]

Depression in adolescence is caused by complex interactions among biological, social, and environmental factors and the prevalence of depression varies across adolescent subpopulations. For instance, girls are much more likely to be diagnosed with depression while boys are more likely to die by suicide,[iv] and suicide rates among Black children have been increasing rapidly, with Black children nearly twice as likely to die by suicide as White children.[v] Early detection and treatment are key to preventing suicide as well as negative, long-term effects of depression in adolescence. For example, adolescents who are screened for depression during a well visit by a pediatrician are more likely to receive a diagnosis of depression or a mood-related disorder in the 6 months after screening.[vi]

Current US Preventive Services Task Force’s guidelines recommend universal screening for depression in adolescents aged 12-18.[vii] Research suggests that while nearly 1 in five school-age adolescents in the U.S. have a diagnosable psychiatric disorder, the majority of mental health problems are undetected and untreated, in part because adolescent depression screening rates remain extremely low.[viii] Screening adolescents for major depressive disorder in primary care settings offers a potential venue for improving universal access to screening, but screening in this setting remains inconsistent with persistent inequalities by race and ethnicity and region.[ix]

Schools are an opportune environment in which to access adolescents for depression screening, particularly those with elevated symptoms of depression as well as those at risk of developing symptoms due to external stressors or internal vulnerabilities.[x] School-based mental health screening may address a number of access-related barriers: they are less stigmatizing, provide an opportunity to target problems before they reach diagnostic criteria, and promote access to care for underserved populations such as minority youth.[xi] School-based screening programs can be effective,[xii] but critical barriers remain.[xiii] Many critical barriers to implementation of depression screening in schools can be addressed via policy. However, because barriers vary across systems and are experienced at different levels of intensity across localities, it is critically important that policy solutions are tailored to the unique needs and circumstances of districts and schools.

WHAT WE DID:

To assess the degree to which school districts and school health professionals in New Jersey are prepared to implement universal depression screening in schools and to better understand what they need to do this well, we conducted interviews with a diverse sample of school administrators, teachers, and child study teams and a statewide survey of school psychologists and school social workers.

WHAT WE ASKED:

We asked interviewees about their experience with student depression in their school and whether they already have procedures in place for screening and referring students to diagnosis and follow up care by a mental health professional. We also inquired about their level of experience and training with adolescent depression screening and common professional and organizational barriers to conducting depression screening in schools. Finally, we asked interviewees for their honest assessment of the feasibility and acceptability of implementing universal depression screening for students in grades 7-12 and what suggestions or recommendations they have for state policymakers.

WHAT WE FOUND:

Both survey respondents and interviewees report that the prevalence of adolescent depression is increasing relative to other common mental health concerns in school. Sixty-two percent of school psychologists and school social workers who responded to the statewide survey indicated that depression was common in their school or district: less common than anxiety (88%), ADHD (86%), and emotional disturbance (72%) but as or more common than conduct and behavioral management problems (62%) and suicidal ideation (27%). However, most are unsure about whether the rise in cases is due to higher incidence of depression or higher rates of detection and identification. Educators and health professionals representing racially diverse districts expressed concerns about rising depression among Black and socioeconomically disadvantaged adolescents, who are also less likely to disclose mental health challenges they experience.

The majority of NJ schools do not currently have an established procedure in place for routinely screening students in grades 7-12 for depression. Of survey respondents, only a handful (less than 5%) indicated that their school or district already has a procedure in place to screen students for depression and only about half received training on this process. Most of the school administrators, teachers, and health professionals interviewed indicated that, although their school or district does not have a formal depression screening process, they currently use an informal procedure whereby a school health professional will have an informal conversation with students who are referred to them by teachers or other school staff to assess risk. If potential risk of depression and/or suicide is detected, the student is referred to further diagnosis and care by a mental health professional. Parents or guardians may be notified when the student is referred to screening or once the school professional conducting the informal screening detects potential risk. Overall, there is considerable variation in how school and districts approach adolescent depression screening.

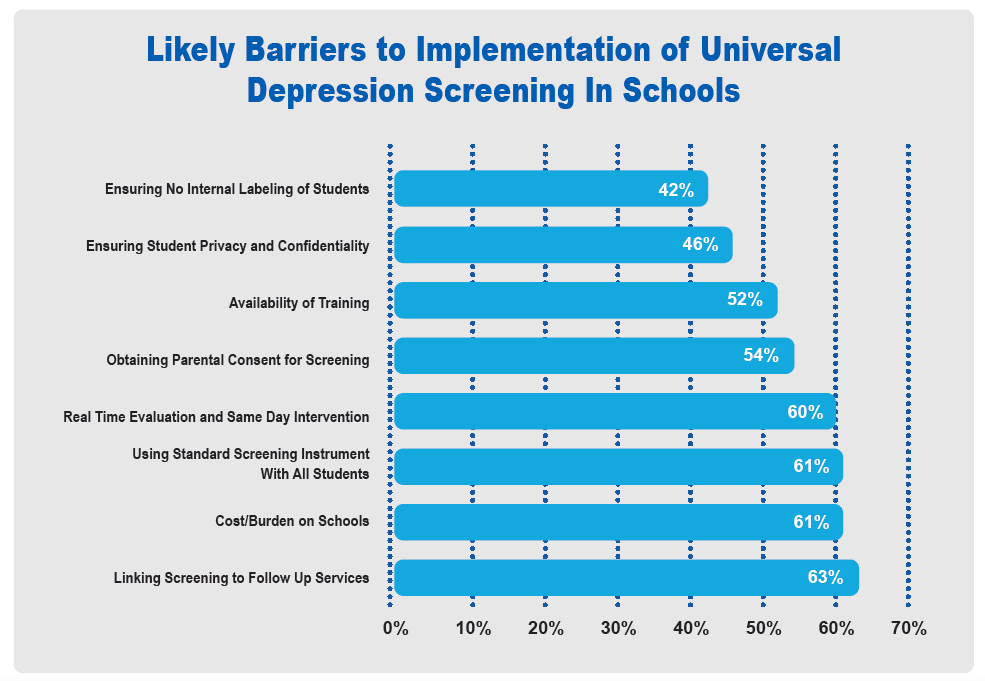

A majority of survey respondents (87%) agree that adopting an evidence-based procedure for conducting adolescent depression screening in schools is very desirable and believe that their school or district will be able to routinely screen all students in grades 7-12 for depression. Most (82%) believe that school or district leaders would approve of universal screening, but only about one-third think that most parents would approve. About half of all respondents expressed concerns about the time and effort needed to implement universal screening and about having access to the resources and assistance they need to do so. Asked to assess which potential barriers to implementation may be of particular concern, most survey respondents expressed concerns regarding the logistics of conducting screening and connecting it to follow up mental health services as well as the additional burden on schools, but also regarding buy-in from parents and protecting students’ privacy (see below). A similar set of concerns also emerged from the interviews with school staff, regardless of school and district characteristics.

When asked what is needed of policymakers to ensure successful implementation of universal adolescent depression screening in schools, survey respondents and interviewees were very clear:

- Explicit guidance to schools regarding the procedure and logistics of conducting screening for adolescent depression

- Clarity regarding the school’s role and responsibilities when screening suggests a potential problem

- Adequate funding for additional qualified staff, training, and resources to administer screenings and interpret results.

WHAT IT MEANS:

It is critical to assess each school or district’s capacity/preparedness to implement adolescent depression screening and use results to inform the development of a school or a district-specific implementation plan

It is unlikely that a single standard approach to screening will provide a good match to the unique circumstances, needs, and student population of each school/district. Allowing schools/districts to select a screening procedure that best fit their circumstances from a limited menu of recommended comparable evidence-based procedures is likely to improve implementation.

Improving access to adolescent depression screening for all students can have a positive impact but only if it is integrated with the provision of other mental health services in schools and in the community.

METHODOLOGY:

Respondents to the online survey (N = 70) were recruited with the help of the New Jersey Association of School Psychologists (NJASP) and the New Jersey Association of School Social Workers (NJASSW). Seventy-five percent of respondents were school psychologists, 15% school social workers, and 10% were counselors or members of child study teams. Eighty percent have been in practice longer than 5 years and 81% served in their current role for over three years (10% between 1-3 years and 8% less than a year). About half were employed in suburban schools or districts, 33% in urban, and the rest in rural schools/districts, with about equal representation across the state (north, central, and south New Jersey). Asked to characterize the socioeconomic profile of the students they serve, 45% of respondents indicated that most students in their school/district are from working class families, and 31% serve students from middle class families, 12% mostly work with students from wealthy families and another 12% primarily serve students from poor families. Questions assessed level of experience and training with adolescent depression screening, common barriers to screening they experience on the job, and their professional assessment of different aspects of implementing universal depression screening in their school or district.

We conducted 15 key informant interviews with an equal number of school counselors and members of child study teams, school principals and district superintendents, and classroom teachers. A purposive sampling strategy was employed to ensure that interviewees represent schools/districts of different sizes and geographical areas and are serving students from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds,.

[i] Office of the Surgeon General (OSG). (2021). Protecting Youth Mental Health: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory. US Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-general-youth-mental-health-advisory.pdf.

[ii] KFF analysis of Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)’s restricted online data analysis system (RDAS), National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), 2018 and 2019, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Data Archive. https://www.kff.org/statedata/mental-health-and-substance-use-state-fact-sheets/new-jersey/.

[iii] Cloutier, R. L., & Marshaall, R. (2021). A dangerous pandemic pair: Covid19 and adolescent mental health emergencies. The American journal of emergency medicine, 46, 776–777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2020.09.008.

[iv] Salk, R. H., Hyde, J. S., & Abramson, L. Y. (2017). Gender differences in depression in representative national samples: Meta-analyses of diagnoses and symptoms. Psychological Bulletin, 143(8), 783–822. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000102.

[v] Bridge JA, Horowitz LM, Fontanella CA, et al. (2018). Age-Related Racial Disparity in Suicide Rates Among US Youths From 2001 Through 2015. JAMA Pediatrics, 172(7):697–699. https://doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.0399.

[vi] Riehm, K. E., Brignone, E., Stuart, E. A., Gallo, J. J., & Mojtabai, R. (2021). Diagnoses and Treatment After Depression Screening in Primary Care Among Youth. American journal of preventive medicine. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2021.09.008.

[vii] Siu, A. L., & US Preventive Services Task Force (2016). Screening for Depression in Children and Adolescents: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Pediatrics, 137(3), e20154467. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-4467.

[viii] Sekhar, D. L., Ba, D. M., Liu, G., & Kraschnewski, J. L. (2019). Major Depressive Disorder Screening Remains Low Even Among Privately Insured Adolescents. The Journal of pediatrics, 204, 203–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.07.086.

[ix] Sekhar, D. L., Schaefer, E. W., Waxmonsky, J. G., Walker-Harding, L. R., Pattison, K. L., Molinari, A., … & Kraschnewski, J. L. (2021). Screening in High Schools to Identify, Evaluate, and Lower Depression Among Adolescents: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA network open, 4(11), e2131836-e2131836. https://doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.31836.

[x] Humphrey, N., & Wigelsworth, M. (2016). Making the case for universal school-based mental health screening. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 21(1), 22-42. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2015.1120051.

[xi] Volpe, R. J., & Briesch, A. M. (2018). Establishing evidence-based behavioral screening practices in US schools. School Psychology Review, 47(4), 396-402. https://doi.org/10.17105/SPR-2018-0047.V47-4.

[xii] Soneson, E., Howarth, E., Ford, T., Humphrey, A., Jones, P. B., Thompson Coon, J., Rogers, M., & Anderson, J. K. (2020). Feasibility of School-Based Identification of Children and Adolescents Experiencing, or At-risk of Developing, Mental Health Difficulties: a Systematic Review. Prevention science, 21(5), 581–603. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-020-01095-6.

[xiii] Burns, J., & Rapee, R. (2021). From barriers to implementation: Advancing universal mental health screening in schools. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools, 31(2), 172-183. https://doi:10.1017/jgc.2021.17.